I originally wrote a version of this article for TakePart.com where I contributed a weekly education post from Sept. 2012-Feb. 2013. Check out the rest of my articles there.

The late (truly) great Shel Silverstein made a truly brilliant point in his poem, Helping.

Some kind of help is the kind of help that helping’s all about

And some kind of help is the kind of help we all can do without!

He wasn’t talking about parents, but he could have been. Helping children is encoded in every parent’s DNA, so how could it be a bad thing?

As Shel pointed out, some help is not at all helpful, especially when the goal is to help kids become independent, fully functioning, young adults. (That is the goal, right?)

Imagine you’re the head teacher in your child’s Life Preparedness Training Course. Not far from the truth. So your long-term educational objective is to teach essential life skills, whatever you consider those to be. You’ve got 18 years to complete the curriculum before your child “graduates.” In terms of life-readiness, with which skills and character traits do you want your child to be equipped? Most parent include: independence, self-reliance, life-long learner, resilience, empathy, self-confidence, etc.

The long-term objectives may be clear, but the method…not always. In fact, sometimes our parental approach directly undermines our objectives. For example, suppose you prioritize “self-reliance,” but your 13 year old can’t for the life of him/her a) get ready for school in a timely fashion, and/or b) manage school challenges and after school obligations. Suppose also, that you have gotten into the habit of doing for your child what you say you want your child to learn to do for himself. Are you teaching your child self-reliance? Or something else?

Now before you head over to the comments section to remind me that not all children are capable of managing their time and responsibilities, let me agree with you. Not all children are 100 percent capable of balancing it all…yet. And some may never get close to managing their lives on their own. But all kids can learn to become more independent. When we require next to nothing of our kids until the time when they can do everything on their own, we are teaching them to be helpless.

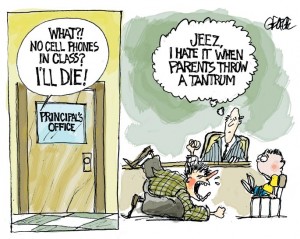

Even a toddler can and should help put away her own books and toys. That’s not a “punishment” nor is it “mean.” Giving them responsibilities is a gift to them, part of our parenting legacy so that they can learn to do for themselves. Self-reliance is the objective. But when parents over-function (do much more than they ought to in relation to the child’s age and ability), then kids tend to under-function (do much less than they are capable of).

And what happens when those kids are at school and teachers expect them to take an active role in their own education? Sadly, it can create problems in individual classrooms and in the overall school climate. Teachers and administrators report that highly capable students (from highly educated parents) frequently lack motivation or initiative. Conversations with educators also indicate that kids whose parents tend to hover have more difficulty working and learning independently. (“They seem to need an awful lot of reassurance that they’re doing it ‘right.’ And even when you give it to them, they seem to be operating with a level of stress that makes it difficult for them to learn and apply what they’ve learned.”)

If you’d like to help your child on the journey toward independence (in school and in life), these tips offer a starting place:

1. Examine your assumptions about your parenting role in terms of helping vs. encouraging independence. If, for example, you believe that “A good parent always does everything for a child,” then you may be over-functioning to the detriment of your child’s development. Take some time to think about ways you can still be a good (even a great) parent without always doing everything for your child.

2. Talk to your child about your pride in his/her increasing maturity. Ask, “In what areas do you feel ready for more independence?” Listen with respect to what your child has to say. Tie together the concepts of added responsibility, added independence, and earned privileges.

3. Incorporate accountability into any discussion on independence and self-reliance. Hold your child accountable for keeping his agreements to family members, teachers, etc. Hold yourself accountable for keeping your agreements. (If that means you agree to not to interfere with homework, then take some deep breaths and stick to it.)

Our parenting journey is basically about teaching our kids to take care of themselves and providing them with age-appropriate opportunities to learn how to rely on their own judgment. If we parent well, eventually they won’t need us. But they’ll always need and use what’ve we taught them.