|

|

October 1, 2013

October is National Bullying Prevention Month. Not sure what we’re expected to work on for the rest of the year, but I’m up for treating people better, at least through Halloween.

Unlike highly successful education campaigns of the past: Don’t Be a Litter Bug and Buckle Up for Safety because Only You Can Prevent Forest Fires, if you go by surveys, our 10+ year war on bullying hasn’t yet reached the tipping point.

There’s no one solution to verbal abuse and the rest of the social garbage that has become the norm for our kids, online and off. Something’s gotta give and each of us has the power to make things better. I never took physics, but I know that everyday nastiness and social aggression adds to the garbage. So it stands to reason that more kindness and respect will move the needle in the other direction.

That’s why, starting today, to honor the good intentions of National Bullying Prevention Month, I’m beginning my own month-long Kindness and Respect Challenge (aka #KindRespect).

Kindness and Respect Challenge Here’s the idea: between now and October 31st, I will actively look for opportunities to be kind and respectful to others. I realize it’s going to take serious anger management and mouth control on my part. I also understand I’m inviting the the Universe to throw a whole lot of “tests” my way, but I’m in and I’ll be reporting my experiences right here every day.

Who’s in with me?

In friendship,

Annie

PS Encourage your kids to join the Kindness and Respect Challenge along with you (and the whole family). Create a #KindRespect chart (could be on the fridge or posted on a wall) in which each one of you who RECEIVES an act of kindness and/or a show of respect from another family writes it down. For example, John might write on the chart, “Trevor helped me with my homework.” Way to go, Trevor! Or Trevor might write, “Mom, made me a snack.” Yay, Mom! At the end of the week, acknowledge the cumulative effects of more kindness and respect in the family. Change happens when we change how we treat each other.

Check out Day 2

April 1, 2013

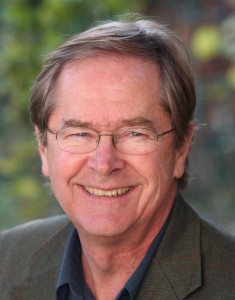

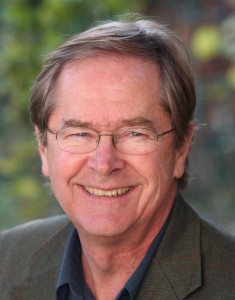

by Rick Ackerly, M. Ed.

Rick Ackerly is a nationally recognized educator and speaker with 45 years experience. He’s served as head of four independent schools, speaks to parent and school groups across the country and at education conferences. Rick is the author of The Genius in Every Child. Visit his blog to learn more about his innovative approach to education and parenting.

Rick Ackerly knows about the genius in children

Last month, waiting at gate B22A at O’Hare a parent told me how frustrated she was with her teenage daughter.

“I’ve tried everything with Julie. I read the parenting books and tried it all, and it’s just not working.”

“What did you try?” I asked.

“You know. I confronted unacceptable behavior; I acknowledged her feelings while insisting on what I wanted. I tried not take it personally, but nothing worked.”

“How do you know it’s not working?” I asked.

She looked at me as if I were either goading her or simply an idiot. “She keeps doing the very things I tell her not to do.”

“With teenagers,” I said. “That is not a sign that it is not working. Adolescents are not constituted to obey. They are wired to disobey. Well, not exactly disobey. They are wired to make their own decisions—not necessarily good ones, but to make them. It is essential for their survival that they practice making decisions and noticing results.”

She, of course, was not relieved to hear this. Raising teenagers can be a nerve- wracking experience, and I have never known a parent who is in the throes of this enterprise to be easily pacified. And anyway, I never got the chance to attempt further consolation, because the boarding process began just as I was delivering my shocking message that “They are wired to disobey.”

I wish I had had the time to tell her about a conversation I had with 18-year-old Allison as I drove her home from a basketball game one Wednesday evening several years ago.

“I listen to my father,” said Allison, “because I have found that he tells me things that turn out to be true. Like ‘Never go out without money,’ he says.”

Allison had needed someone to talk to. Last Saturday night there had been a party where some of her classmates got drunk and trashed the house of a classmate.

She went on: “I wish I could talk to the parents of my friends and tell them how to talk to their kids. I wish they would tell them things like ‘Never go out without money.’ There we are at Starbucks and they’re all, ‘Allison, can you pay for this? I didn’t bring any money,’ and I go, ‘Sure.’ But it get’s annoying. They do pay me back, but it’s annoying. Parents ought to be careful what they tell their kids, so that when they give them advice, the kids will listen. What those kids did to that house was gross.”

“But you don’t always do what your father says, do you?”

“No, but when he talks, I do listen. Sure, it makes me mad when he tells me to get off Facebook and to start doing my homework, but I know he is telling me the right thing. That’s the point. I know it is the right thing for him to tell me. It makes him mad when I don’t do it right away, but that’s the way it’s supposed to be between parents and their teenagers. I know he’s right. I just have to do it myself. He has become like an authority. When he speaks I listen.”

Don’t all parents want to become “like an authority?” Listen to Allison. She is on to something very important.

Until age five, it is important for parents to back up their statements—with force if necessary. If a parent says: “No, you can’t have a candy cane before dinner,” then it is very important that the child does not eat a candy cane before dinner. “Eight o’clock bedtime” has to mean: In bed by eight. Period. If a parent says it’s bad for you and then let’s you do it, how can you trust such a parent? Why should a child listen to such a parent?

However, by age thirteen, the human brain is working to develop and consolidate the part of the brain that makes decisions—the pre-frontal cortex. By 18 the teenage brain has all the circuitry of an adult brain, but not enough practice. They know drinking to excess is not good for you, and that trashing a house is very bad, but the adolescent mind is open to other possibilities which must be tested to be “known.” Close relationships with adult authorities are important for helping kids know which end is up. If kids listen to parents it is because parents have proven that they are authorities worth listening to.

December 31, 2012

I originally wrote this article for TakePart.com where I write a weekly education post. Check out the rest of my articles there.

Homework doesn't make kids smarter, it mostly just keeps them busy and stresses them out The long holiday break is almost over. I hope you and your kids made the most of the delights of the season. And that includes time to relax together as a family, kids and parents, savoring the freedom from school assignments. Yes, I’m an educator, but I am no fan of homework. Especially not obligatory daily assignments that drill students on information and skills they’ve already mastered. Practice makes perfect. But over-practice makes for soul-crushing boredom and it turns kids off of education.

From my way of thinking, homework, if given at all, ought to be assigned sparingly. After all, kids have had a long day in class. They’re not machines. They need a break. And, yes, they need to play. Coming home from school every day to face a mountain of homework is dispiriting.

If a teacher assigns homework, students and parents ought to be confident that there’s a very good reason for the assignment, and a high likelihood that it will yield tangible benefits for the student. What kind of assignments are those? The ones that include:

- a creative challenge

- the opportunity to reinforce a new concept presented during class

- practice using the concept for problem-solving

The result? S-T-R-E-T-C-H-I-N-G the student’s mind and transforming a new idea into an Ah-ha! learning experience. When homework offers these opportunities kids respond eagerly because, as learners, they win. This makes them eager to learn more. (And if that isn’t the ultimate goal of education, I don’t know what is.)

The alphabet coloring homework sheets my son received for 26 weeks during his kindergarten year were busy work. There was no mind stretching during those coloring sessions. Though, as I recall, there was some healthy resistance and a pointed challenge: “Mom, why do I have to do this?”

Why indeed? Teachers aren’t sadists. They must believe homework benefits their students. But is that really the case? According to Alfie Kohn, educator, educational critic, and author of The Homework Myth, “…there is no evidence that… kids who have better grades and test scores have them because they’ve had to do more academic assignments after a full day in school. (Also) there isn’t a shred of evidence to demonstrate that homework has any nonacademic advantages, such as teaching self-discipline and responsibility or teaching kids good work habits.”

And yet the homework continues piling up and the stress it causes in kids, and in families, is heartbreaking. If it feels like your child is spending inordinate amounts of time on homework, here are some steps you might take:

1. Find out what your district’s homework policy is. The student handbook usually includes guidelines that describe how many minutes of homework per evening per grade level. Compare the guidelines to reality.

2. Talk with other parents whose kids have the same teacher as your child. Sometimes the issue is “too much homework.” When that’s the case, parents have the right and responsibility to talk with teachers and let them know the impact all those assignments are having at home.

3. Talk with your child’s teacher. Sometimes, the issue isn’t the amount of homework. Sometimes it’s your child’s ability to complete the assignment in a timely fashion. Ask your child’s teacher, “How much time did you expect that assignment to take?” If what you hear is: “10-15 minutes” and your child spent 45+ minutes, then you and the teacher may have a new topic of conversation. For example: “How can we work together to help this student (my child) be more successful and efficient in his/her work? Is an evaluation for learning differences an option we should consider?”

4. Down with busy work! If teachers are assigning homework that clearly falls into the Busy Work category, speak up to the teacher (calmly and respectfully, of course), to other parents, and at PTA meetings.

A child’s mind is a terrible thing to waste. So is a child’s time to relax, dream, and be a kid without the ever-present dark cloud of “homework” hanging over their heads.

Here’s wishing you and your family all the best in 2013, More laughter. More opportunities to help others. More creative inspiration. And less homework.

June 27, 2012

The following is an excerpt from the keynote speech I delivered yesterday at the 18th Annual Character Education Conference in St. Louis.

Showing we care is a good thing We are human and by definition that means we are vulnerable. Unlike any other creatures, we are aware of our own mortality and so we experience worry and grief. We also know the joys of working together and supporting each other. We celebrate. We nurture. We protect. Because we can be so loving, we sometimes suffer rejection and loss. We trust. We open up and give of ourselves, and sometimes we feel betrayed.

In Teen World, aggressive anger is OK, but real vulnerability, are you kidding me? Teens get clear messages from peers to stay away from vulnerable emotions… especially in public. If you are hurt, don’t show it. If you are disappointed, don’t show it. If you love someone, don’t show it. Slip up and let some vulnerability bleed through the veneer and you are a baby. A wuss. A wimp. You are a pathetic loser.

Wrong! I am a human being.

Teaching kids to be good people means helping them understand and accept the broad spectrum of human emotions. Being afraid is not a cause for shame. Tears are no less acceptable than laughter. It’s all part of the package. If my tears are an honest expression of sadness, grief, joy, why should I hide them from you. Or be embarrassed in front of you?

We are mistaken when we buy into the notion that vulnerability is weakness. Our strength comes from our vulnerability. This may seem counter-intuitive since the word vulnerable derives from the Latin vulnere (meaning “to wound”) A wounded individual is hardly at her strongest, but I see emotions in a different light. Our feelings are our most authentic responses to life. If I am hurt, I cry. If someone is with me, my tears are likely to remind him of sadness he has felt. By responding to me, he acknowledges his own humanity. But if he mocks my tears or tries to push them aside, that indicates he is afraid to respond with compassion. Afraid to show how he has been touched. That he holds himself back from experiencing his full humanity makes me want to reach out and teach, because he is in desperate need of an education.

Unless we can embrace the vulnerable emotions underneath the Anger Lid, it is impossible for us to reach our full human potential. When we feel hurt and choose instead to plaster over our vulnerability with indifference, cool detachment or social aggression, we build walls between us. But if, instead, we are willing to honor our vulnerability, then we can strengthen our connections to other people. Isn’t that exactly what we’re trying to teach our students by creating positive school climates? When we recognize on a deep level that we all experience the same emotions, how can we not empathize with each other? How can we help but reach out in friendship to a person who needs a friend?

Schools that encourage kids to be humane graduate people of good character who are also, good judges of character. When it comes to how we treat each other, the graduates of those schools, have learned to set the bar very high for themselves and for their peers.

— Older Posts »

| |