|

|

May 18, 2013

"I just want this to stop! But I don't know what to do." I originally wrote a version of this article for TakePart.com where I’ve contributed education posts. Check out the rest of my articles there.

My email from teens lessens on weekends. This may seem counter-intuitive since kids have more time to connect with friends. But school is where most of the social garbage gets dumped and spread around.

If you read your teen’s texts (I don’t recommend this unless you’ve got real cause for snooping. If not, please respect healthy boundaries.) you’ll mostly find innocuous blips of conversation. But sometimes your child’s circle of friends—and frenemies—can be intentionally cruel and toxic. That’s when parents need to be aware of what’s happening. Our job is to to help kids manage their intense emotions while teaching them appropriate ways to respond to friends who aren’t acting like friends.

Of course, many teens aren’t fans of sharing friendship issues with parents. They assume adult involvement will cause loss of computer and phone access. Or parents’ stepping in will just make things worse. Sometimes those fears are well placed, especially when adults don’t act responsibly. That’s why it’s important to know when and how to help a child who’s being harassed.

More: A Bully’s Paradise: Hidden Halls, Dark Corners and No Supervision

Here are some signs that your child may be having problems with peers. He/she:

- seems upset, anxious, or worried after reading text messages or spending time on social networking sites.

- gets defensive or clams up when you ask about school in general or about certain friendships.

- exhibits a change in appetite, sleep patterns, a dramatic dip in grades, a sudden reluctance to go to school, or a loss of interest in activities he/she previously enjoyed.

If you’ve been observing any of these signs over time, talk with your child, even if he/she insists that everything is “fine.” You know what fine looks like. If what you’re seeing doesn’t look fine, then trust your instincts—but don’t turn this into an interrogation. That will add stress and make it less likely that your child will want to talk to you.

Instead, you might begin the conversation with a straightforward observation. For example: “I’ve noticed that you seem upset whenever you come home from Emily’s house.” Then close your mouth, look into your child’s eyes with compassion, and listen. Hopefully, your calm, loving demeanor will (eventually) encourage your child to open up about what’s going on.

If other kids are targeting your child, be empathetic. Then find out what your child has already tried in an attempt to improve the situation. If he/she has not yet spoken directly to the aggressor, suggest it as an option. Teach your child to let others know that he/she deserves to be treated with respect. Tell your child that staying silent in the face of injustice rarely leads to more justice. On the other hand, when a formerly passive victim stands up for him/herself, the aggressor may realize they’ve been disrespectful. They may stop. Of course, sometimes it takes more than that.

If your child has delivered a clear message repeatedly and the harassment persists, it’s time to get the school involved. If your child wants to talk with an adult at school without your help, let him/her go for it. It’s great training for life. If your child would prefer for you to be there, then be there.

Before the meeting, check out BullyPolice.org and educate yourself on the anti-bullying legislation that exists at your state level. At the meeting, let your child take the lead when talking about his/her experience. Request to see a copy of the school district’s anti-bullying policy.

If the peer harassment persists, demand another meeting with the principal, yourself, and the parents of the child(ren) who has been harassing your child. If the principal and/or the other kids’ parents are unconcerned (“It’s just kid stuff”) or if you feel like you’re getting a runaround (“We’ll work on it”), don’t waste your breath. Go over the principal’s head to the superintendent. Name names. Be a pain. Do not allow yourself to be silenced. Do not stop the pressure until the harassment stops.

Every school has a legal and moral responsibility to make sure that all students are treated with respect at all times. When parents hold schools accountable, schools are more likely to do their job well.

November 8, 2012

I originally wrote a version of this article for TakePart.com, an interactive publisher and the digital arm of Participant Media. Check out my weekly Education posts there.

"Help! I'm drowning in social garbage!" I’ve been answering teen email since 1997. The ongoing Q&A has made me an expert on the social garbage many 11-17 year olds slog through every day. Typical teen questions include:

- What do you do if your friend is mad at you but won’t tell you why?

- What do you do if people are spreading rumors about you and no one believes that they aren’t true?

- What do you do when friends pressure you to do stuff you don’t want to do, but you’re afraid not to because they’ll make fun of you?

Sound familiar? These might be the same issues we once dealt with, but our children aren’t responding to them the way we did before social media. When 21st-century kids experience peer conflicts, online and off, they typically respond with a level of social aggression (aka verbal violence) that damages individuals in profound ways and pollutes school climates everywhere.

In September I spoke with nearly a thousand students at a couple of international schools, one in Singapore and another in Chiang Mai, Thailand. We talked about Real Friends vs. the Other Kind, based on my Middle School Confidential series. In each presentation the kids and I discussed tough issues like: stress, peer approval addiction, and the brain’s occasional habit of working against our desire to do the right thing. Even though I was 7,000 miles from home, the comments and questions coming from these students expressed the same conflicts and emotional confusion I’ve heard repeatedly from kids in San Jose, St. Louis, and Philly.

Back in the last century, when we had a problem with someone at school, we went home for dinner with the family, did homework, and watched TV. Sometimes we even read a book to take our minds off school and social garbage. The next morning in class combatants were usually less combative and we were all better able to concentrate on whatever we were expected to learn.

Today’s kids are mind-melded with peers 24/7. School and home are equally conducive for frantic texting and getting more people involved in the drama du jour. Status anxiety regularly submerges so much mental real estate, our students are often flooded with destructive emotions. They can’t think clearly when they’re upset. No one can. Which is why the adults who live and work with kids need to actively teach kids to be good people, otherwise, their moral compasses will be calibrated solely by their equally clueless peers. (Not a pretty thought!)

April 27, 2012

As an educator who’s been receiving student email from around the world for the past 15 years, I can tell you that kids are desperately seeking adult leadership to deal with school bullying. (See my review of the movie BULLY) The way 6th-8th graders describe it, in often heart-breaking terms, is that there is “no point in talking to teachers or the principal about this, because they do NOTHING.”

At this point, when the problem has been sufficiently identified so that everyone knows exactly what bullying is, any further talk talk talk is the same as doing nothing. Talk is cheap. School assemblies with outside speakers may not be ‘cheap’ but they do allow a school administration that doesn’t prioritize character education in any discernible way to tell distraught parents: “We’re handling it. We had an anti-bullying assembly.”

Piffle.

Even the most inspirational student assembly has no power to change a school culture. Not by its lonesome. Because a school’s culture is a living, breathing entity. Each school day, moment-by-moment, and each night on social media, all individuals within that school community contribute to the culture. If a school is truly serious about challenging the Culture of Cruelty you’ve got to do way more than talk. You need to call a community-wide meeting and give each stake-holder an opportunity to speak – that includes all students, teachers, coaches, administrators, support staff (bus drivers, office personnel, after school program staff, etc.). Conduct a Truth and Reconciliation session. Get real. Express the hurt. The anger. The frustration. Cop to the injustice. Take responsibility for what you’ve done and what you’ve failed to do. Apologize. Make amends. Work together to develop strategies for moving forward. Once the strategy for a culture of inclusion is in place, do not fail for one moment to foster it so it can take root and thrive.

November 22, 2010

In a rare but not unprecedented move, we sent our intrepid Time Traveler back to the late 1980s to report on the historic role of parents in their children’s education. What she uncovered may be hard for us 21st Century parents to believe, but we’ve verified her account by cross-referencing it with archival documents as well as first hand reports from today’s Elders and young adults who swear this is the way it was. Her report is excerpted here:

On weekdays during the 1980s, parents kissed their kids goodbye at the front door and sent them out into the world. The children either marched themselves to a bus stop, walked to school or rode a bike (yes they had helmets, though nowhere as cool as the ones we’ve got) From the moment they turned the corner, parents could not directly communicate with their kids.

WARNING: If you find yourself feeling anxious reading the above, we recommend putting your head between your knees and breathing in slowly through your nose and exhaling slowing through you mouth. If that doesn’t alleviate your symptoms, shut down your computer and take a warm bath, with or without bubbles.

All during morning classes, lunchtime, recess, afternoon classes and onsite after school programs, kids were incommunicado. You’re probably wondering, “What if the kid left a lunch, a book or assignment at home? How could Mom or Dad rush to school to help if they didn’t know there was a problem?” The teachers and school administrators of the ’80s had a simple answer for that one: If the kid doesn’t bring something (s)he needs to schoool, then the kid figures it out and deals with the consequences. Period.

Cruel and unusual punishment, granted, but that’s the way it was.

In case you’re shaking your head thinking, “That sounds like a lockdown!” 20th Century schools weren’t entirely lacking compassion. For example, if a kid complained of a headache, (s)he asked the teacher’s permission to go to the office where she’d plead her case to the school nurse and likely be given an opportunity to rest quietly. If the nurse felt the situation warranted it, the school placed a call home or to the parents’ office and the problem was solved. Are they for real?! Think of the precious moments lost using that antiquated system!

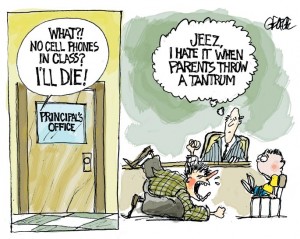

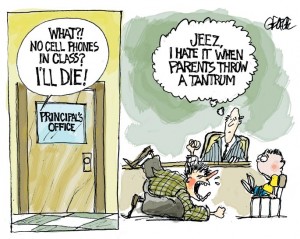

Today, thankfully, we can call and/or text our kids at any time, including 9-3 and we do…often! Yet, apparently, some schools are cracking down on in-class cellphone use. They say the constant ringing and buzzing is a distraction to teachers and any students interested in receiving an education. (What kind of lame excuse is that?) In addition, schools limiting students’ cellphone access also justify it by saying the policy reduces in-class cheating and cyber-bullying. Hmm. Well, maybe we can see some logic there, but who cares?! Schools have no right to prioritize education over a parent’s access to their children. This is the 21st Century, Ms. Principal, and these are Anxious Times. Today, thankfully, we can call and/or text our kids at any time, including 9-3 and we do…often! Yet, apparently, some schools are cracking down on in-class cellphone use. They say the constant ringing and buzzing is a distraction to teachers and any students interested in receiving an education. (What kind of lame excuse is that?) In addition, schools limiting students’ cellphone access also justify it by saying the policy reduces in-class cheating and cyber-bullying. Hmm. Well, maybe we can see some logic there, but who cares?! Schools have no right to prioritize education over a parent’s access to their children. This is the 21st Century, Ms. Principal, and these are Anxious Times.

Your thoughts?

— Older Posts »

| |